How Dividends and Reinvestment Can Protect Your Investment in a Down Market

When I talk about investing with people, I always get the same comment. "It just sounds too risky. What if the price goes down?" I mean, it's a valid point, right?

Nobody wants to lose money. The whole point of investing is to make money. And unfortunately, the risk of losing money is enough to keep some people out of the stock market completely. If only there was a way to avoid the pain of seeing your market value decline, while still getting all the benefits of a roaring bull market. What if I told you that there is a way? Well, sort of.

Dividend Growth Stocks: Rewarding Shareholders In Any Market

If you've read some of my other posts about investing, you may have picked up by now that I typically invest in dividend growth stocks. So not only am I usually looking for stocks with a better than average yield, but I also take into consideration a company's consistency of increasing their dividends on an annual basis, and projecting whether I think it is practical for them to continue to do so into the future. So how does investing in dividend yielding stocks protect me in the event of a market downturn? Aren't these stocks going to sink in value like the rest of them?

Likely, yes. However, it's not hard to see that even while the price keeps dropping, you are still being rewarded for holding the stock. Assuming you've picked a well-established company that is still generating enough income to continue their dividend payments and growth, you will be rewarded by receiving dividend payments no matter how low the stock price gets. Now, sometimes it can be hard to determine whether a company is able to weather the economic conditions that are likely to be the cause of a significant drop in the market well enough to continue to pay and grow their dividends, so I often look to a group of stocks called the dividend aristocrats to identify these types of companies. A dividend aristocrat is a company that has paid and increased their dividend annually for 25 consecutive years. These companies have exhibited that they are able to continue to reward shareholders no matter what the current economic cycle.

Clearly, receiving dividend payments can ease the pain of a loss in the value of your investment a bit, but in the event of a recession or prolonged bear market, the rate at which the market is dropping can be much higher than the rate at which you're receiving dividend payments. In this case, isn't it just better to stay out of the market and just hold cash? Not necessarily. In addition to investing in dividend growth stocks, there is one strategic step further that can further protect your investment in a downturn, and really "pay dividends" (pun intended) in the long run.

Dividend Reinvestment: Bear Market Insurance?

I like to think of dividend reinvestment as an extra layer of protection on top of my investment in dividend growth stocks. If you are not familiar, a dividend reinvestment plan, or DRIP for short, automatically takes the dividend paid to you on a stock or fund, and reinvests back into the same holding at it's current share price. Typically, even if you're not receiving enough in a dividend payment to purchase a full share, fractional shares can be issued (this can depend on the plan or brokerage). What this does is create a compounding effect - each dividend that is reinvested will increase your number of shares, which in turn increases your next dividend. And in the case of a downward market, your dividend will be reinvesting into more and more shares as the share price drops.

That sounds great, right? Well, I tend to like visuals better, so I've set up a real life example of this happening to illustrate this effect.

But first, I want to get a few thoughts out of the way.

I want to acknowledge that ideally, you do not want the price of your stock to go down. Best case scenario, you make your purchase right at the lowest price, and ride the roller coaster all the way up, watching the value of your investment grow and grow. But in the stock market, there are ups, as we've seen over the past decade, and there are downs (think Great Depression, dotcom bubble, financial crisis, etc.). As much as we all would like to, there is no predicting when these ups and downs can occur. Chances are, if you've been waiting for one of these "downs" to happen over the last decade to make an entrance into the market, you've probably missed out on a lot of gains you could have captured if you had just made your entrance and not tried to time the market. So thought #1: Ups and downs will happen - don't try to time the market!

In the event of an all out bear market, chances are the value of your stocks is going to fall significantly. From January 2000 to July 2002, the S&P 500 dropped from 1,500 points all the way down to just above 800 points. Then, from July 2007 to January 2009, an almost identical drop occurred again. However, what happened between 2002 and 2007, and between 2009 and current day? Stocks have trended upwards. Historically, every bear market has been followed by a bull market, with the market currently at near-highs, even after recent short term turbulence. So that brings me to thought #2: I invest with the assumption that the stock market, as a whole, will increase in value in the long run.

This assumption is what gives me confidence in my investing strategy, and if you don't share this same outlook, then you may want to take a different strategy. However, I would like to challenge you to think this: if the market were to not continue upward over time, and instead move downward toward zero, wouldn't there likely be bigger problems than losing money? Likely, an indefinite drop in the market would be the result of a near-collapse of American business, which surely would cause some type of economic and political unrest. But I will move on past this doomsday scenario.

Visual Example: Taking Cash vs. Dividend Reinvestment Over a Decade (Plus)

So originally, I wanted to look at the effect of dividend re-investment on a single holding that more or less mirrored the ups and downs of the S&P 500 index over the past decade. The only issue is, over the past decade, the direction has basically been nothing but up. That doesn't make for a very good analysis - basically any stock I chose would show the DRIP scenario far outpacing the non-DRIP scenario, since the re-invested shares would be doing nothing but appreciating in value the whole time.

So I expanded my window a little bit. I still wanted to wrap up the example on today's date (or at least on June 11, 2019 when I pulled the data and ran the analysis), but I figured it would be an interesting idea to choose just about the absolute worst time to have entered the market in the last ten or so years. With this in mind, I chose to start my experiment with a hypothetical investment of $1,000 on an entrance date of October 1, 2007.

Why October 1, 2007? Take a look below at a chart of the S&P 500 index right around this date.

Source: Yahoo! Finance

Guess what date corresponds with that high right before the drop all the way from over 1,500 to less than 680. Bingo! Investing on October 1, 2007 meant that in a year and a half, your principal was worth well below half what you started with.

Now, I was too young to pay any attention to the stock market at this time, but I'm sure hat there were plenty of people saying to sell all the way down to the bottom. Not to mention, those who just stayed out of the market completely probably looked like the smartest of anyone. But what happened if you just rode it out? Let's take a look.

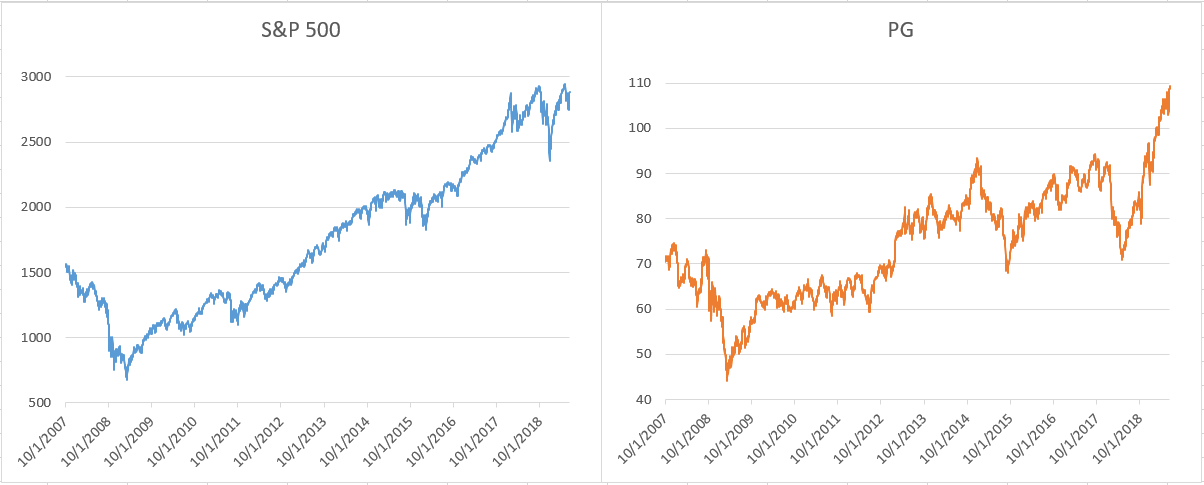

For the sake of making the dividend reinvestment timing and calculations easier, instead of using the S&P 500 index, I chose to use a stock that mirrored the ups and downs closely. To speed up the data collection and calculation process, I also simulated the dividend reinvestment on the date of declaration instead of the actual dividend payment date. I assume that the short time difference did not make a huge impact. Further, I wanted to choose a dividend aristocrat for the example, so I ended up choosing to use Procter & Gamble (PG) as the investment. Check out a comparison of the price charts of the S&P 500 index and PG over the period of the experiment below.

Not identical, of course, but both experienced a peak in price on October 1, 2007, followed by a significant drop over the next year and a half. Both bottomed out on March 9, 2009, followed by a generally upward trend through the current date, with PG experiencing a bit more turbulence along the way.

With the stock picked, I made my hypothetical investment: 14 shares of PG on October 1, 2007 at the closing price for the day, $70.91, for a total investment of $992.74.

I then ran two models side by side. The first - I reinvested all dividends received. This is the scenario that follows my personal strategy. The second scenario - instead of reinvesting the dividends, I assumed the cash went into a non-interest-bearing account - aka, cash or a checking account. However, I still include the accumulated value of this cash in the total value of the second scenario.

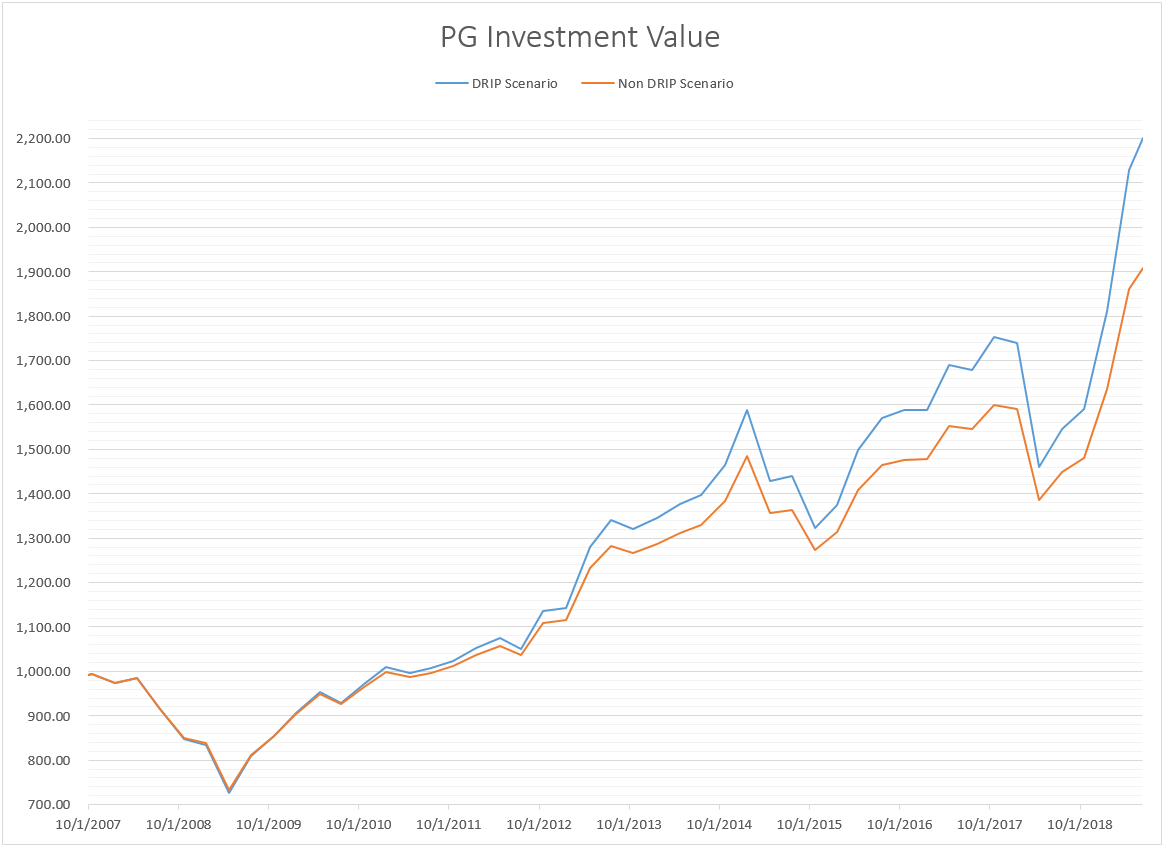

I will let a visual of the two scenarios tell the rest of the story.

Let's talk through this. It's hard to see due to the size of the graph, but for a while, the non-DRIP scenario actually has a slightly higher value than the DRIP scenario. This happens right around a year in, and lasts for about a year in duration. The reason for this is that when the price is falling, the shares that were picked up via reinvestment further decreased in value until bottoming - meaning during this time, even though the cash was just sitting idle in value, it was a better return than the reinvested shares.

However, with the price dropping, the same dividend amount was able to pick up a higher number of shares upon reinvestment. Put another way - if I own one share of a company, and reinvest a $1 dividend while the stock is worth $5, I will pick up .2 shares upon reinvestment. But if that price had dropped to $4 at the time of reinvestment, that reinvestment would have picked up .25 shares. So now, I have 1.25 shares, which will give me a dividend of $1.25, instead of 1.2 shares giving me a dividend of $1.20. Not a huge difference, but over time the effect compounds into a larger variance in both share count and dividend amount.

Back to the PG example. The values of both scenarios stay very close as the price climbs back from the bottom in March of 2009, and then the compounding effect of the dividend reinvestment starts to take control as the market began to really rebound in 2012. Past this point, even with some 20% drops along the way, the DRIP scenario stays well ahead in value. On the final date of the model, June 11, 2019, the DRIP scenario had a value of $2,200, while the non-DRIP scenario had a value of $1,910. The difference is almost $300 on a sub $1,000 investment - and that's even after starting the investment on the absolute worst day to enter a position in this time frame. Further, the initial investment of 14 shares has now turned to 20.12 shares in the DRIP example.

Conclusion

Visually, the result is clear. If you have confidence that businesses will thrive into the future and the stock market will continue an upward trend, an investment in a sound, dividend producing company, coupled with a dividend reinvestment strategy looks to be a good investment.

Maybe this sounds obvious to you, but you have trouble choosing a "sound" company that will continue to follow the market trend and pay, and increase, dividends over time. I mean, I'm sure companies like GE or Ford seemed like a "safe" company at one point to many investors (I'm guilty of the latter).

In addition to researching the dividend aristocrats, an easy option for someone who is not confident in their stock picking skills would be to invest in a low cost mutual fund or ETF. A few of my personal favorites that don't require a minimum investment over the price of one share are the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO) and the Vanguard High Dividend Yield ETF (VYM). I hold both in my portfolio, which you can view here.

In closing, just remember to realize that there is always a risk you can lose money. Maybe you're entering the stock market at the absolute worst time, and there could be a huge drop tomorrow. But even in an example where that was the case, the result of sticking it out with a good, dividend producing company over time compensated for the short term drop, as significant as it was.

What role do dividend stocks play in your portfolio? Do you re-invest your dividends, or do you prefer to choose what you do with the cash? I'd love to hear some other views on the manner!

- FI Anon

Disclaimer: I am not a financial professional. The above post is my personal strategy on investing, and is in no way financial advice. I hope you enjoyed reading, and consider the concepts I have highlighted above, but please do your own research before investing.

Nobody wants to lose money. The whole point of investing is to make money. And unfortunately, the risk of losing money is enough to keep some people out of the stock market completely. If only there was a way to avoid the pain of seeing your market value decline, while still getting all the benefits of a roaring bull market. What if I told you that there is a way? Well, sort of.

Dividend Growth Stocks: Rewarding Shareholders In Any Market

If you've read some of my other posts about investing, you may have picked up by now that I typically invest in dividend growth stocks. So not only am I usually looking for stocks with a better than average yield, but I also take into consideration a company's consistency of increasing their dividends on an annual basis, and projecting whether I think it is practical for them to continue to do so into the future. So how does investing in dividend yielding stocks protect me in the event of a market downturn? Aren't these stocks going to sink in value like the rest of them?

Likely, yes. However, it's not hard to see that even while the price keeps dropping, you are still being rewarded for holding the stock. Assuming you've picked a well-established company that is still generating enough income to continue their dividend payments and growth, you will be rewarded by receiving dividend payments no matter how low the stock price gets. Now, sometimes it can be hard to determine whether a company is able to weather the economic conditions that are likely to be the cause of a significant drop in the market well enough to continue to pay and grow their dividends, so I often look to a group of stocks called the dividend aristocrats to identify these types of companies. A dividend aristocrat is a company that has paid and increased their dividend annually for 25 consecutive years. These companies have exhibited that they are able to continue to reward shareholders no matter what the current economic cycle.

Clearly, receiving dividend payments can ease the pain of a loss in the value of your investment a bit, but in the event of a recession or prolonged bear market, the rate at which the market is dropping can be much higher than the rate at which you're receiving dividend payments. In this case, isn't it just better to stay out of the market and just hold cash? Not necessarily. In addition to investing in dividend growth stocks, there is one strategic step further that can further protect your investment in a downturn, and really "pay dividends" (pun intended) in the long run.

Dividend Reinvestment: Bear Market Insurance?

I like to think of dividend reinvestment as an extra layer of protection on top of my investment in dividend growth stocks. If you are not familiar, a dividend reinvestment plan, or DRIP for short, automatically takes the dividend paid to you on a stock or fund, and reinvests back into the same holding at it's current share price. Typically, even if you're not receiving enough in a dividend payment to purchase a full share, fractional shares can be issued (this can depend on the plan or brokerage). What this does is create a compounding effect - each dividend that is reinvested will increase your number of shares, which in turn increases your next dividend. And in the case of a downward market, your dividend will be reinvesting into more and more shares as the share price drops.

That sounds great, right? Well, I tend to like visuals better, so I've set up a real life example of this happening to illustrate this effect.

But first, I want to get a few thoughts out of the way.

I want to acknowledge that ideally, you do not want the price of your stock to go down. Best case scenario, you make your purchase right at the lowest price, and ride the roller coaster all the way up, watching the value of your investment grow and grow. But in the stock market, there are ups, as we've seen over the past decade, and there are downs (think Great Depression, dotcom bubble, financial crisis, etc.). As much as we all would like to, there is no predicting when these ups and downs can occur. Chances are, if you've been waiting for one of these "downs" to happen over the last decade to make an entrance into the market, you've probably missed out on a lot of gains you could have captured if you had just made your entrance and not tried to time the market. So thought #1: Ups and downs will happen - don't try to time the market!

In the event of an all out bear market, chances are the value of your stocks is going to fall significantly. From January 2000 to July 2002, the S&P 500 dropped from 1,500 points all the way down to just above 800 points. Then, from July 2007 to January 2009, an almost identical drop occurred again. However, what happened between 2002 and 2007, and between 2009 and current day? Stocks have trended upwards. Historically, every bear market has been followed by a bull market, with the market currently at near-highs, even after recent short term turbulence. So that brings me to thought #2: I invest with the assumption that the stock market, as a whole, will increase in value in the long run.

This assumption is what gives me confidence in my investing strategy, and if you don't share this same outlook, then you may want to take a different strategy. However, I would like to challenge you to think this: if the market were to not continue upward over time, and instead move downward toward zero, wouldn't there likely be bigger problems than losing money? Likely, an indefinite drop in the market would be the result of a near-collapse of American business, which surely would cause some type of economic and political unrest. But I will move on past this doomsday scenario.

Visual Example: Taking Cash vs. Dividend Reinvestment Over a Decade (Plus)

So originally, I wanted to look at the effect of dividend re-investment on a single holding that more or less mirrored the ups and downs of the S&P 500 index over the past decade. The only issue is, over the past decade, the direction has basically been nothing but up. That doesn't make for a very good analysis - basically any stock I chose would show the DRIP scenario far outpacing the non-DRIP scenario, since the re-invested shares would be doing nothing but appreciating in value the whole time.

So I expanded my window a little bit. I still wanted to wrap up the example on today's date (or at least on June 11, 2019 when I pulled the data and ran the analysis), but I figured it would be an interesting idea to choose just about the absolute worst time to have entered the market in the last ten or so years. With this in mind, I chose to start my experiment with a hypothetical investment of $1,000 on an entrance date of October 1, 2007.

Why October 1, 2007? Take a look below at a chart of the S&P 500 index right around this date.

Source: Yahoo! Finance

Guess what date corresponds with that high right before the drop all the way from over 1,500 to less than 680. Bingo! Investing on October 1, 2007 meant that in a year and a half, your principal was worth well below half what you started with.

Now, I was too young to pay any attention to the stock market at this time, but I'm sure hat there were plenty of people saying to sell all the way down to the bottom. Not to mention, those who just stayed out of the market completely probably looked like the smartest of anyone. But what happened if you just rode it out? Let's take a look.

For the sake of making the dividend reinvestment timing and calculations easier, instead of using the S&P 500 index, I chose to use a stock that mirrored the ups and downs closely. To speed up the data collection and calculation process, I also simulated the dividend reinvestment on the date of declaration instead of the actual dividend payment date. I assume that the short time difference did not make a huge impact. Further, I wanted to choose a dividend aristocrat for the example, so I ended up choosing to use Procter & Gamble (PG) as the investment. Check out a comparison of the price charts of the S&P 500 index and PG over the period of the experiment below.

Not identical, of course, but both experienced a peak in price on October 1, 2007, followed by a significant drop over the next year and a half. Both bottomed out on March 9, 2009, followed by a generally upward trend through the current date, with PG experiencing a bit more turbulence along the way.

With the stock picked, I made my hypothetical investment: 14 shares of PG on October 1, 2007 at the closing price for the day, $70.91, for a total investment of $992.74.

I then ran two models side by side. The first - I reinvested all dividends received. This is the scenario that follows my personal strategy. The second scenario - instead of reinvesting the dividends, I assumed the cash went into a non-interest-bearing account - aka, cash or a checking account. However, I still include the accumulated value of this cash in the total value of the second scenario.

I will let a visual of the two scenarios tell the rest of the story.

Let's talk through this. It's hard to see due to the size of the graph, but for a while, the non-DRIP scenario actually has a slightly higher value than the DRIP scenario. This happens right around a year in, and lasts for about a year in duration. The reason for this is that when the price is falling, the shares that were picked up via reinvestment further decreased in value until bottoming - meaning during this time, even though the cash was just sitting idle in value, it was a better return than the reinvested shares.

However, with the price dropping, the same dividend amount was able to pick up a higher number of shares upon reinvestment. Put another way - if I own one share of a company, and reinvest a $1 dividend while the stock is worth $5, I will pick up .2 shares upon reinvestment. But if that price had dropped to $4 at the time of reinvestment, that reinvestment would have picked up .25 shares. So now, I have 1.25 shares, which will give me a dividend of $1.25, instead of 1.2 shares giving me a dividend of $1.20. Not a huge difference, but over time the effect compounds into a larger variance in both share count and dividend amount.

Back to the PG example. The values of both scenarios stay very close as the price climbs back from the bottom in March of 2009, and then the compounding effect of the dividend reinvestment starts to take control as the market began to really rebound in 2012. Past this point, even with some 20% drops along the way, the DRIP scenario stays well ahead in value. On the final date of the model, June 11, 2019, the DRIP scenario had a value of $2,200, while the non-DRIP scenario had a value of $1,910. The difference is almost $300 on a sub $1,000 investment - and that's even after starting the investment on the absolute worst day to enter a position in this time frame. Further, the initial investment of 14 shares has now turned to 20.12 shares in the DRIP example.

Conclusion

Visually, the result is clear. If you have confidence that businesses will thrive into the future and the stock market will continue an upward trend, an investment in a sound, dividend producing company, coupled with a dividend reinvestment strategy looks to be a good investment.

Maybe this sounds obvious to you, but you have trouble choosing a "sound" company that will continue to follow the market trend and pay, and increase, dividends over time. I mean, I'm sure companies like GE or Ford seemed like a "safe" company at one point to many investors (I'm guilty of the latter).

In addition to researching the dividend aristocrats, an easy option for someone who is not confident in their stock picking skills would be to invest in a low cost mutual fund or ETF. A few of my personal favorites that don't require a minimum investment over the price of one share are the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO) and the Vanguard High Dividend Yield ETF (VYM). I hold both in my portfolio, which you can view here.

In closing, just remember to realize that there is always a risk you can lose money. Maybe you're entering the stock market at the absolute worst time, and there could be a huge drop tomorrow. But even in an example where that was the case, the result of sticking it out with a good, dividend producing company over time compensated for the short term drop, as significant as it was.

What role do dividend stocks play in your portfolio? Do you re-invest your dividends, or do you prefer to choose what you do with the cash? I'd love to hear some other views on the manner!

- FI Anon

Disclaimer: I am not a financial professional. The above post is my personal strategy on investing, and is in no way financial advice. I hope you enjoyed reading, and consider the concepts I have highlighted above, but please do your own research before investing.

Comments

Post a Comment